Xuanzang

Early Life and Education

Xuanzang, also known as Hsüan-tsang, was a renowned Chinese Buddhist monk, scholar, traveler, and translator who lived during the Tang dynasty. Born in 602 CE in Chenliu, Henan province, Xuanzang was the youngest of four children in a scholarly family. His early education was rooted in Confucianism, but he was drawn to Buddhism, a religion that was flourishing in China at the time. His elder brother, Changjie, was a Buddhist monk, and Xuanzang followed in his footsteps, becoming a novice monk at the age of thirteen.

Xuanzang's early monastic education took place at the Jingtu Monastery in Luoyang, where he was exposed to various Buddhist texts. However, he found the Chinese translations of these texts to be inconsistent and incomplete, which sparked his desire to travel to India to study Buddhism at its source. This ambition was further fueled by his interest in the Mahayana and Theravada schools, and his desire to resolve discrepancies between different Buddhist doctrines.

Journey to India

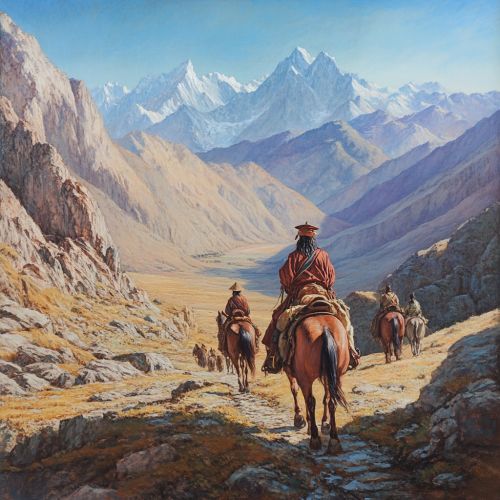

In 629 CE, Xuanzang embarked on a perilous journey to India, defying a travel ban imposed by the Tang government. His journey, which lasted for 17 years, took him across the vast deserts and treacherous mountain ranges of Central Asia. He traveled through the Gobi Desert, the Tianshan Mountains, and the Pamir Plateau, reaching the Indian subcontinent via the Khyber Pass.

Xuanzang's travels are meticulously documented in his work, the "Great Tang Records on the Western Regions" (Da Tang Xiyu Ji), which provides invaluable insights into the geography, culture, and religious practices of the regions he visited. His journey took him to the major Buddhist centers of learning, including Nalanda, where he studied under the guidance of the renowned scholar Silabhadra.

Studies and Achievements in India

During his time in India, Xuanzang immersed himself in the study of Buddhist philosophy, logic, and metaphysics. He mastered Sanskrit and studied the major Buddhist texts, including the Prajnaparamita, Yogacara, and Abhidharma treatises. His studies at Nalanda, a premier center of Buddhist learning, were particularly influential, and he became well-versed in the doctrines of the Madhyamaka and Yogacara schools.

Xuanzang's intellectual pursuits were not limited to Buddhism; he also engaged with the broader intellectual currents of Indian philosophy, including Hinduism and Jainism. His interactions with Indian scholars enriched his understanding of the cultural and religious landscape of the subcontinent.

Return to China and Translation Work

In 645 CE, Xuanzang returned to China, bringing with him a vast collection of Buddhist texts, relics, and images. His return was celebrated, and he was received with great honor by Emperor Taizong of Tang. Xuanzang's primary focus upon his return was the translation of the Buddhist scriptures he had acquired. He established a translation bureau at the Daci'en Temple in Chang'an, where he worked with a team of scholars to translate the texts into Chinese.

Xuanzang's translation work was monumental, resulting in the translation of over 1,300 fascicles of Buddhist scriptures. His translations are noted for their accuracy and fidelity to the original texts, and they played a crucial role in the dissemination of Buddhist teachings in China. Among his most significant translations are the "Heart Sutra" and the "Diamond Sutra," which remain central to East Asian Buddhism.

Legacy and Influence

Xuanzang's contributions to Buddhism and Chinese culture are profound. His translations laid the foundation for the development of the Faxiang school of Buddhism in China, which is based on the Yogacara teachings. His travelogue, the "Great Tang Records on the Western Regions," is a critical historical source that provides insights into the political, cultural, and religious dynamics of Central Asia and India during the 7th century.

Xuanzang's life and journey have inspired numerous works of art and literature, most notably the classic Chinese novel "Journey to the West," which fictionalizes his pilgrimage to India. His legacy continues to be celebrated in both China and India, where he is revered as a symbol of intercultural exchange and scholarly pursuit.