Water table

Introduction

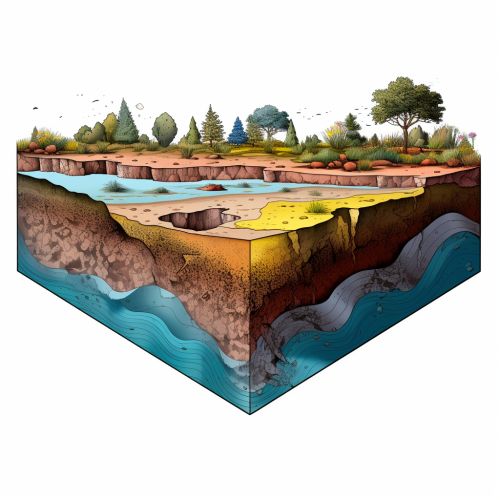

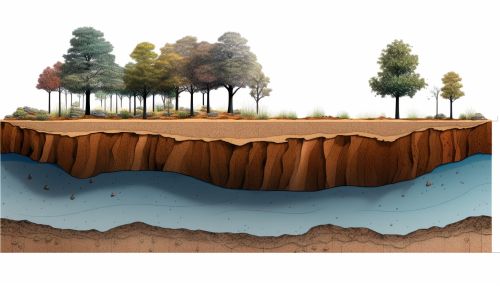

The water table is the upper surface of the zone of saturation in the ground, where the pores and fractures of the soil, sediment, and rocks are saturated with water. The water table separates the zone of saturation below from the zone of aeration above. It is an important concept in hydrogeology, the study of water's distribution and movement in the Earth's crust.

Formation and Characteristics

The water table is formed by the infiltration of precipitation or other surface water into the ground, a process known as recharge. The rate of recharge can be influenced by various factors, including the permeability of the soil or rock, the amount and intensity of precipitation, and the evaporation and transpiration rates.

The water table is not a static feature; it fluctuates over time in response to changes in weather, climate, and human activities. During periods of heavy rainfall or snowmelt, the water table may rise as more water infiltrates the ground. Conversely, during dry periods or times of heavy groundwater extraction, the water table may fall.

The depth of the water table can vary greatly from place to place and from season to season. It can be close to the ground surface in low-lying areas or in regions with high rainfall, and several meters below the surface in arid regions or on hillsides.

Measurement and Monitoring

The depth to the water table can be measured in a well, a piezometer, or an observation borehole. These measurements are often taken at regular intervals to monitor changes in the water table over time. This monitoring is important for managing water resources, predicting droughts and floods, and assessing the impacts of climate change and human activities on groundwater resources.

Groundwater levels can also be monitored remotely using satellite-based technologies, such as the Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE) satellites. These satellites measure changes in the Earth's gravity field, which can be used to infer changes in groundwater storage.

Water Table and Groundwater Flow

The water table is not flat but has a slope, or hydraulic gradient. This gradient is determined by the balance between recharge and discharge and the permeability of the subsurface materials. Groundwater flows from areas of high hydraulic head (where the water table is high) to areas of low hydraulic head (where the water table is low). The direction and speed of groundwater flow can have important implications for the transport of contaminants in the subsurface.

Human Impacts on the Water Table

Human activities can significantly impact the water table. Over-extraction of groundwater for irrigation, industrial use, or public water supply can lower the water table, a condition known as groundwater depletion. This can lead to a number of problems, including land subsidence, reduced streamflow, and degradation of water quality.

Conversely, activities such as irrigation, canal leakage, or the injection of treated wastewater into the ground can raise the water table. This can lead to waterlogging of agricultural land and other problems.