Tonghak Rebellion

Background and Origins

The Tonghak Rebellion, also known as the Donghak Peasant Revolution, was a significant peasant uprising in Korea that took place in 1894. The rebellion was primarily driven by the widespread discontent among the peasantry due to oppressive taxation, corruption, and the influence of foreign powers. The term "Tonghak" translates to "Eastern Learning," which was a religious and social movement founded by Choe Je-u in 1860. This movement sought to counter the influence of Western Christianity and promote indigenous Korean values and social reforms.

The origins of the Tonghak movement can be traced back to the mid-19th century when Korea was experiencing significant internal and external pressures. Internally, the Joseon Dynasty was grappling with corruption, economic hardship, and social inequality. Externally, the encroachment of Western powers and Japan posed a threat to Korea's sovereignty. Choe Je-u, the founder of Tonghak, sought to address these issues by advocating for a return to traditional Korean values and the establishment of a more just and equitable society.

Causes of the Rebellion

The Tonghak Rebellion was fueled by a combination of social, economic, and political factors. The following are some of the primary causes:

Social Inequality

The rigid class structure of the Joseon Dynasty created significant social stratification, with the yangban (nobility) enjoying privileges and the commoners, particularly the peasants, bearing the brunt of exploitation. The peasants were subjected to heavy taxation, forced labor, and arbitrary exactions by local officials.

Economic Hardship

Economic conditions in Korea during the late 19th century were dire. Natural disasters, poor harvests, and economic mismanagement led to widespread poverty and famine. The peasants, who were already struggling to make ends meet, were further burdened by the state's demands for taxes and tributes.

Corruption and Maladministration

Corruption among local officials was rampant. The yangban class often abused their power, extorting money and resources from the peasantry. This corruption eroded the legitimacy of the government and fueled resentment among the common people.

Foreign Influence

The increasing presence of foreign powers, particularly Japan and Western nations, was seen as a threat to Korea's sovereignty. The imposition of unequal treaties and the influx of foreign goods disrupted the local economy and created a sense of national crisis.

Religious and Ideological Motivations

The Tonghak movement, with its emphasis on social justice, equality, and national sovereignty, resonated with the disaffected peasantry. The movement's religious teachings, which blended elements of Confucianism, Buddhism, and indigenous Korean beliefs, provided a moral and ideological framework for the rebellion.

Course of the Rebellion

The Tonghak Rebellion can be divided into several key phases:

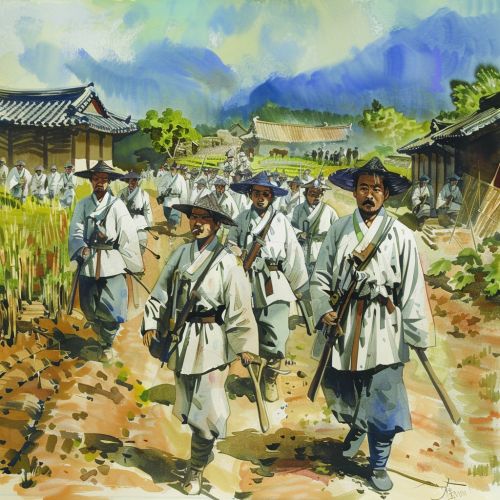

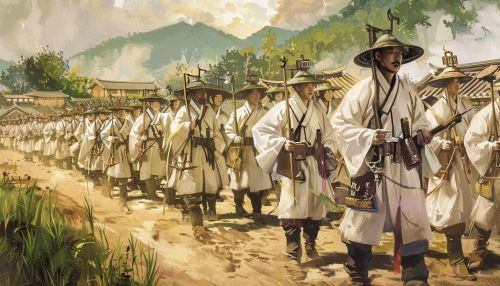

Initial Uprising

The rebellion began in January 1894 in the Jeolla Province, a region known for its fertile land and dense peasant population. The initial uprising was led by Jeon Bong-jun, a charismatic leader who rallied the peasants with promises of social reform and the eradication of corruption. The rebels quickly gained control of several towns and villages, establishing their own administrative structures.

Expansion and Consolidation

As the rebellion gained momentum, it spread to other provinces, including Chungcheong and Gyeongsang. The rebels organized themselves into a disciplined fighting force, employing guerrilla tactics and leveraging their knowledge of the local terrain. They also sought to win the support of local communities by implementing reforms, such as redistributing land and reducing taxes.

Government Response

The Joseon government, initially caught off guard by the scale of the rebellion, eventually mobilized its military forces to suppress the uprising. However, the government's efforts were hampered by internal divisions and the lack of a cohesive strategy. The rebels managed to inflict several defeats on government forces, further emboldening their cause.

Foreign Intervention

The escalating rebellion drew the attention of foreign powers, particularly Japan and China, both of which had vested interests in Korea. In June 1894, Japan dispatched troops to Korea under the pretext of protecting its nationals and restoring order. This intervention marked the beginning of the First Sino-Japanese War, as China also sent troops to counter Japan's influence.

Decline and Suppression

The entry of Japanese forces into Korea marked a turning point in the rebellion. The Japanese military, better equipped and organized, launched a series of offensives against the Tonghak rebels. Despite their initial successes, the rebels were gradually overwhelmed by the superior firepower and tactics of the Japanese. By the end of 1894, the rebellion had been largely suppressed, and its leaders, including Jeon Bong-jun, were captured and executed.

Aftermath and Impact

The Tonghak Rebellion had far-reaching consequences for Korea and the broader region:

Political Reforms

In the wake of the rebellion, the Joseon government implemented a series of reforms aimed at addressing some of the grievances that had fueled the uprising. These reforms, known as the Gabo Reforms, included measures to modernize the administration, reduce corruption, and improve the legal rights of commoners. However, these reforms were largely driven by Japanese influence and were met with mixed reactions from the Korean populace.

Foreign Domination

The rebellion and the subsequent Sino-Japanese War marked a significant shift in the balance of power in East Asia. Japan emerged as the dominant power in Korea, leading to the eventual annexation of Korea by Japan in 1910. The period of Japanese rule had profound and lasting effects on Korean society, economy, and culture.

Legacy of the Tonghak Movement

The Tonghak movement, despite its defeat, left a lasting legacy in Korean history. It highlighted the deep-seated social and economic issues facing the country and inspired subsequent movements for social justice and national independence. The movement also laid the groundwork for the later development of the Cheondoism, a religious movement that evolved from Tonghak and continued to advocate for social reform and national sovereignty.

See Also

References

- Kim, Djun Kil. *The History of Korea*. Greenwood Publishing Group, 2005.

- Eckert, Carter J., et al. *Korea Old and New: A History*. Harvard University Press, 1990.

- Palais, James B. *Confucian Statecraft and Korean Institutions: Yu Hyongwon and the Late Choson Dynasty*. University of Washington Press, 1996.