Organ rejection

Introduction

Organ rejection is a significant complication that can occur after an organ transplant. It involves the recipient's immune system recognizing the transplanted organ as foreign and mounting an immune response against it. This response can damage or destroy the transplanted organ, leading to transplant failure and potentially life-threatening complications. Understanding the mechanisms, types, diagnosis, and management of organ rejection is crucial for improving transplant outcomes.

Mechanisms of Organ Rejection

Organ rejection is primarily mediated by the immune system, which is designed to protect the body from foreign invaders such as bacteria, viruses, and other pathogens. When an organ is transplanted, the recipient's immune system may recognize the donor organ as foreign due to differences in HLA antigens. This recognition triggers an immune response aimed at eliminating the perceived threat.

Cellular Immunity

Cellular immunity involves T lymphocytes (T cells) that recognize and respond to foreign antigens presented by antigen-presenting cells (APCs). The primary mechanisms include:

- **Direct Allorecognition**: Donor APCs present donor antigens to recipient T cells, leading to T cell activation and proliferation.

- **Indirect Allorecognition**: Recipient APCs process and present donor antigens to recipient T cells, resulting in a similar immune response.

Humoral Immunity

Humoral immunity involves B lymphocytes (B cells) and the production of antibodies against donor antigens. These antibodies can bind to antigens on the surface of the transplanted organ, leading to complement activation and subsequent tissue damage.

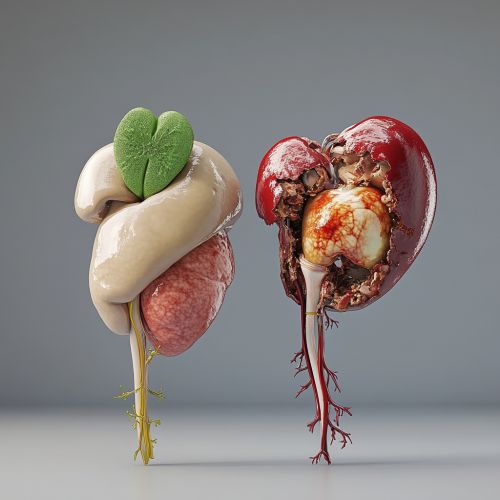

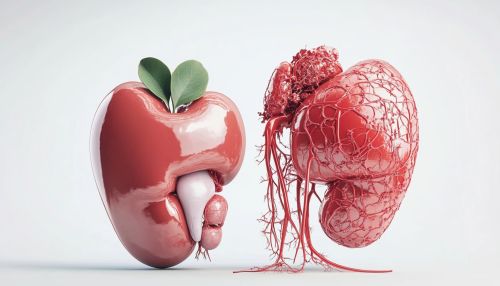

Types of Organ Rejection

Organ rejection can be classified into three main types based on the timing and underlying mechanisms:

Hyperacute Rejection

Hyperacute rejection occurs within minutes to hours after transplantation. It is mediated by pre-existing antibodies in the recipient that recognize and bind to antigens on the donor organ. This leads to rapid complement activation, endothelial damage, and thrombosis, resulting in immediate graft failure.

Acute Rejection

Acute rejection typically occurs within the first few weeks to months post-transplant. It can be further divided into:

- **Cellular Acute Rejection**: Mediated by T cells that infiltrate the graft and cause tissue damage.

- **Antibody-Mediated Rejection (AMR)**: Involves the production of donor-specific antibodies (DSAs) that target the graft, leading to complement activation and tissue injury.

Chronic Rejection

Chronic rejection develops over months to years and is characterized by progressive graft dysfunction. It involves both cellular and humoral immune responses, leading to fibrosis, vascular changes, and eventual graft failure.

Diagnosis of Organ Rejection

Early and accurate diagnosis of organ rejection is essential for effective management. Diagnostic methods include:

Clinical Assessment

Monitoring for signs and symptoms of graft dysfunction, such as decreased organ function, pain, fever, and swelling.

Laboratory Tests

- **Serum Creatinine**: Elevated levels may indicate kidney rejection.

- **Liver Function Tests**: Abnormal results can suggest liver rejection.

- **Cardiac Biomarkers**: Elevated levels may indicate heart rejection.

Imaging Studies

- **Ultrasound**: Can detect structural changes and blood flow abnormalities.

- **Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)**: Provides detailed images of the graft and surrounding tissues.

Biopsy

A biopsy involves obtaining a tissue sample from the transplanted organ for histological examination. It is the gold standard for diagnosing rejection and can differentiate between cellular and antibody-mediated rejection.

Management of Organ Rejection

Management strategies for organ rejection aim to suppress the immune response and preserve graft function. These include:

Immunosuppressive Therapy

Immunosuppressive drugs are the cornerstone of rejection management. They can be classified into several categories:

- **Calcineurin Inhibitors (CNIs)**: Such as Cyclosporine and Tacrolimus, which inhibit T cell activation.

- **Antiproliferative Agents**: Such as Mycophenolate mofetil and Azathioprine, which inhibit lymphocyte proliferation.

- **Corticosteroids**: Such as Prednisone, which have broad immunosuppressive effects.

- **mTOR Inhibitors**: Such as Sirolimus and Everolimus, which inhibit T cell proliferation and function.

Plasmapheresis

Plasmapheresis involves the removal of antibodies from the recipient's blood, which can be effective in treating antibody-mediated rejection.

Intravenous Immunoglobulin (IVIG)

IVIG can neutralize antibodies and modulate immune responses, making it useful in managing antibody-mediated rejection.

Monoclonal Antibodies

Monoclonal antibodies, such as Rituximab and Basiliximab, target specific components of the immune system and can be used to treat rejection.

Prevention of Organ Rejection

Preventing organ rejection involves a combination of strategies aimed at minimizing immune activation and maintaining graft tolerance:

HLA Matching

Careful matching of donor and recipient HLA antigens can reduce the risk of rejection by minimizing immune recognition of the graft as foreign.

Induction Therapy

Induction therapy involves the use of potent immunosuppressive agents at the time of transplantation to prevent early rejection. Common agents include:

- **Antithymocyte Globulin (ATG)**: Depletes T cells and reduces immune activation.

- **Interleukin-2 Receptor Antagonists**: Such as Basiliximab, which block T cell activation.

Maintenance Immunosuppression

Long-term immunosuppressive therapy is essential to prevent rejection. It typically involves a combination of drugs to achieve adequate immunosuppression while minimizing side effects.

Monitoring and Early Intervention

Regular monitoring of graft function and immune status allows for early detection and treatment of rejection, improving outcomes.

Future Directions

Research in organ transplantation is ongoing, with several promising areas aimed at improving outcomes and reducing rejection rates:

Tolerance Induction

Tolerance induction involves strategies to promote immune tolerance to the graft, potentially reducing the need for long-term immunosuppression. Approaches include:

- **Mixed Chimerism**: Inducing a state where donor and recipient immune cells coexist.

- **Regulatory T Cells (Tregs)**: Enhancing the function of Tregs to suppress immune responses against the graft.

Biomarkers

Identifying biomarkers that predict rejection risk and response to therapy can improve personalized management and outcomes.

Gene Therapy

Gene therapy approaches aim to modify the recipient's immune system or the donor organ to reduce rejection risk.