Hemochromatosis

Introduction

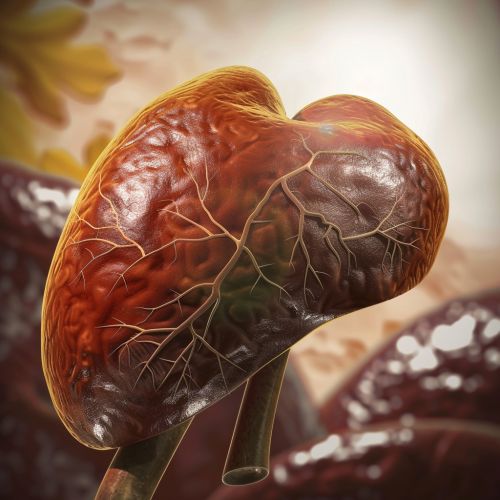

Hemochromatosis is a genetic disorder characterized by excessive absorption of dietary iron, resulting in iron overload in various organs. This condition can lead to serious health issues, including liver disease, heart problems, and diabetes. Hemochromatosis is often asymptomatic in its early stages, making early diagnosis and management crucial to prevent complications.

Types of Hemochromatosis

Hemochromatosis can be classified into several types based on its genetic and clinical characteristics:

Hereditary Hemochromatosis

Hereditary hemochromatosis (HH) is the most common form and is primarily caused by mutations in the HFE gene. The most frequent mutations associated with HH are C282Y and H63D. Individuals who are homozygous for the C282Y mutation are at the highest risk of developing iron overload.

Juvenile Hemochromatosis

Juvenile hemochromatosis is a rare form that presents in adolescence or early adulthood. It is caused by mutations in the HJV gene (hemojuvelin) or the HAMP gene (hepcidin antimicrobial peptide). This type of hemochromatosis is characterized by severe iron overload and early onset of symptoms.

Neonatal Hemochromatosis

Neonatal hemochromatosis is a rare and severe form that affects newborns. It is not caused by genetic mutations but is believed to be an alloimmune condition, where maternal antibodies attack the fetal liver. This leads to extensive iron deposition in the liver and other tissues.

Secondary Hemochromatosis

Secondary hemochromatosis, also known as acquired hemochromatosis, occurs due to external factors such as repeated blood transfusions, chronic liver disease, or excessive dietary iron intake. Unlike hereditary forms, secondary hemochromatosis is not caused by genetic mutations.

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of hemochromatosis involves dysregulation of iron homeostasis. In healthy individuals, iron absorption is tightly regulated by the hormone hepcidin, which is produced by the liver. Hepcidin inhibits iron absorption by binding to the iron transporter ferroportin on enterocytes and macrophages, leading to its internalization and degradation.

In hemochromatosis, mutations in genes such as HFE, HJV, or HAMP result in decreased hepcidin production or function. This leads to unregulated iron absorption from the diet and increased release of iron from macrophages. The excess iron is deposited in various organs, causing tissue damage and dysfunction.

Clinical Manifestations

The clinical manifestations of hemochromatosis vary depending on the extent and duration of iron overload. Common symptoms and signs include:

- Fatigue and weakness

- Joint pain, particularly in the metacarpophalangeal joints

- Abdominal pain

- Loss of libido and impotence in men

- Menstrual irregularities in women

- Skin hyperpigmentation, often described as a "bronze" appearance

- Hepatomegaly and liver cirrhosis

- Diabetes mellitus

- Cardiomyopathy and heart failure

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of hemochromatosis involves a combination of clinical evaluation, laboratory tests, and genetic testing.

Laboratory Tests

Key laboratory tests for diagnosing hemochromatosis include:

- Serum ferritin: Elevated levels indicate increased iron stores.

- Transferrin saturation: High levels suggest increased iron absorption.

- Liver function tests: Abnormal results may indicate liver damage.

Genetic Testing

Genetic testing for mutations in the HFE gene is essential for confirming the diagnosis of hereditary hemochromatosis. Testing for other genes such as HJV and HAMP may be necessary in cases of juvenile hemochromatosis.

Imaging

Imaging studies such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can assess iron deposition in the liver and other organs. MRI is particularly useful for evaluating the extent of iron overload and monitoring treatment response.

Management

The primary goal of hemochromatosis management is to reduce iron overload and prevent organ damage. Treatment strategies include:

Phlebotomy

Phlebotomy, or bloodletting, is the mainstay of treatment for hereditary hemochromatosis. Regular removal of blood reduces iron levels by depleting iron stores. The frequency of phlebotomy sessions depends on the severity of iron overload and the patient's response to treatment.

Chelation Therapy

Chelation therapy involves the use of medications that bind to iron and facilitate its excretion. This approach is typically reserved for patients who cannot tolerate phlebotomy or have secondary hemochromatosis due to repeated blood transfusions. Common chelating agents include deferoxamine, deferasirox, and deferiprone.

Dietary Modifications

Patients with hemochromatosis are advised to avoid iron-rich foods and supplements. Additionally, they should limit alcohol consumption, as it can exacerbate liver damage. Vitamin C supplements, which enhance iron absorption, should also be avoided.

Complications

If left untreated, hemochromatosis can lead to several serious complications:

- Liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma

- Diabetes mellitus

- Heart failure and arrhythmias

- Hypogonadism and infertility

- Arthritis and joint damage

Prognosis

The prognosis of hemochromatosis depends on the stage at which the condition is diagnosed and the effectiveness of treatment. Early diagnosis and regular phlebotomy can prevent most complications and allow patients to lead a normal life. However, advanced iron overload with organ damage may result in irreversible complications and reduced life expectancy.

Research and Future Directions

Ongoing research in hemochromatosis focuses on understanding the genetic and molecular mechanisms underlying the disorder. Advances in gene therapy and targeted treatments hold promise for more effective management of iron overload. Additionally, efforts are being made to improve early detection and screening programs to identify at-risk individuals before the onset of symptoms.

See Also