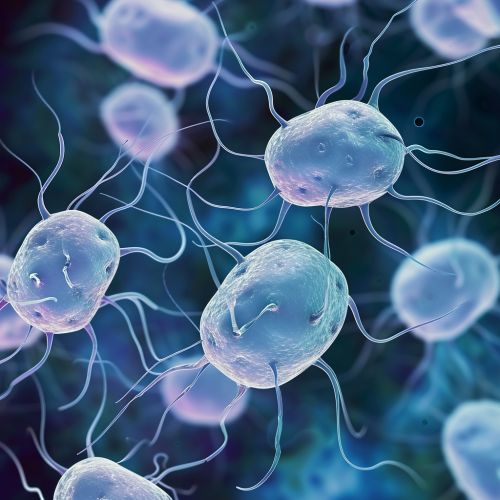

Giardia lamblia

Introduction

Giardia lamblia, also known as Giardia intestinalis, is a flagellated parasite that colonizes and reproduces in the small intestine, causing giardiasis. The parasite attaches to the epithelium by a ventral adhesive disc, and reproduces via binary fission. Giardiasis does not spread via the bloodstream, nor does it spread to other parts of the gastrointestinal tract, but remains confined to the lumen of the small intestine[1].

Life Cycle

Giardia lamblia undergoes two stages during its life cycle. The active form inside the host is a trophozoite, which is anaerobic. It reproduces inside the host's small intestine. After it is excreted by the host via feces, it morphs into a hardy, disease-spreading cyst stage, which can survive outside the host for long periods[2].

Transmission

Giardia lamblia is transmitted via the fecal-oral route. Primary routes are ingestion of cyst-contaminated water, food, or by the fecal-oral route (hands or fomites). In the wilderness, backpackers are advised to treat water from streams and rivers due to the risk of Giardia contamination[3].

Symptoms and Diagnosis

Symptoms of Giardia lamblia infection include diarrhea, malaise, excessive gas, steatorrhea, epigastric pain, bloating, nausea, diminished interest in food, possible (but rare) vomiting, and weight loss. Stools may be foul-smelling but do not contain blood or mucus. Symptoms typically begin 1–2 weeks after infection and may wane and reappear cyclically. Symptoms are caused by the parasitic attachment to the small intestine leading to malabsorption and can last for up to six weeks[4].

Treatment

The most commonly used drug for treatment is metronidazole, a 5-nitroimidazole drug derived from the antibiotic azomycin. Metronidazole is a prodrug; its cytotoxic action is activated in the anaerobic environment of the protozoan[5].

Epidemiology

Giardia lamblia is a common cause of waterborne disease. It is found worldwide and within every region of the United States. The CDC reports more than 20,000 cases per year, but the actual number is suspected to be much higher because the disease is underreported and many cases are asymptomatic[6].

See Also

- ↑ Adam, RD (2001). "Biology of Giardia lamblia". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 14 (3): 447–75.

- ↑ Thompson, RC (2000). "Giardiasis as a re-emerging infectious disease and its zoonotic potential". International Journal for Parasitology. 30 (12–13): 1259–67.

- ↑ Monis, PT; Andrews, RH; Mayrhofer, G; Ey, PL (2003). "Molecular systematics of the parasitic protozoan Giardia intestinalis". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 20 (9): 1135–44.

- ↑ Farthing, MJ (1996). "Giardiasis". Gastroenterology Clinics of North America. 25 (3): 493–515.

- ↑ Upcroft, P; Upcroft, JA (2001). "Drug targets and mechanisms of resistance in the anaerobic protozoa". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 14 (1): 150–64.

- ↑ Thompson, RC (2004). "The zoonotic significance and molecular epidemiology of Giardia and giardiasis". Veterinary Parasitology. 126 (1–2): 15–35.