Chemoreception

Overview

Chemoreception refers to the physiological processes through which organisms respond to chemical stimuli. This process is fundamental to the survival of many species, enabling them to detect food, predators, mates, and other environmental cues. Chemoreception encompasses two main sensory modalities: olfaction, or the sense of smell, and gustation, or the sense of taste.

Mechanism of Chemoreception

Chemoreception involves the detection of chemical stimuli by specialized sensory cells known as chemoreceptors. These chemoreceptors can be found in various parts of an organism, including the nasal cavity and the taste buds on the tongue in humans. The chemoreceptors are activated by specific chemical molecules, known as ligands, which bind to the receptors and trigger a series of biochemical reactions that ultimately result in the generation of a nerve impulse. This nerve impulse is then transmitted to the brain, where it is interpreted as a specific smell or taste.

Olfaction

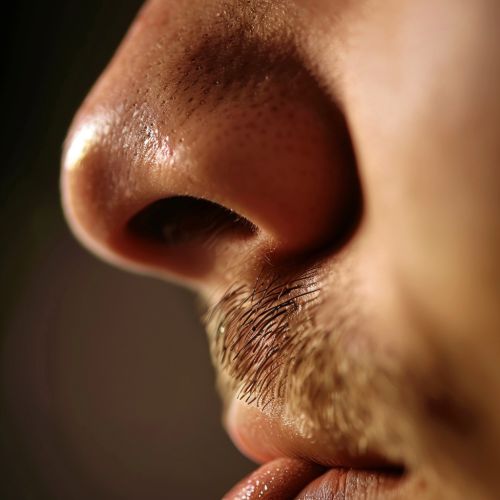

Olfaction, or the sense of smell, is a form of chemoreception that involves the detection of volatile chemical compounds in the environment. The process begins in the nasal cavity, where inhaled air carries these compounds to the olfactory epithelium, a specialized tissue located at the top of the nasal cavity. This tissue contains millions of olfactory receptor neurons, each of which expresses a unique olfactory receptor protein. When a volatile compound binds to this receptor, it triggers a signal transduction pathway that results in the generation of a nerve impulse. This impulse is then transmitted to the olfactory bulb, a structure located at the base of the brain, where it is processed and relayed to other areas of the brain for further processing and interpretation.

Gustation

Gustation, or the sense of taste, is another form of chemoreception that involves the detection of soluble chemical compounds in food and drink. These compounds are detected by taste buds, which are clusters of sensory cells located on the tongue and other parts of the oral cavity. Each taste bud contains multiple taste receptor cells, which are activated by specific types of taste molecules. These include sweet, sour, salty, bitter, and umami (savory) tastes. When a taste molecule binds to a taste receptor, it triggers a series of biochemical reactions that result in the generation of a nerve impulse. This impulse is then transmitted to the gustatory cortex, a region of the brain responsible for the perception of taste.

Evolution of Chemoreception

The evolution of chemoreception has played a crucial role in the survival and diversification of species. The ability to detect and respond to chemical cues in the environment has enabled organisms to find food, avoid predators, select mates, and adapt to changing environmental conditions. The evolution of chemoreception is thought to have occurred through a process of gene duplication and diversification, leading to the emergence of a wide array of chemoreceptors capable of detecting a diverse range of chemical stimuli.

Chemoreception in Different Species

Chemoreception is not limited to humans and other mammals. Many other species, including insects, fish, and birds, also rely on chemoreception for survival. For example, insects use chemoreception to locate food sources, find mates, and navigate their environment. Fish use chemoreception to detect changes in water chemistry, which can indicate the presence of food or predators. Birds use chemoreception to identify suitable nesting sites and to recognize their own offspring.

Clinical Significance

Disorders of chemoreception can have a significant impact on quality of life. Conditions such as anosmia (loss of smell) and ageusia (loss of taste) can result from damage to the chemoreceptors or the neural pathways that transmit chemosensory information to the brain. These conditions can be caused by a variety of factors, including head injury, viral infections, exposure to toxic chemicals, and certain medications. Treatment options for chemosensory disorders are currently limited, but ongoing research in this field holds promise for the development of new therapeutic strategies.